When Technology and Government Collide

From Wired:

Feds Leapfrog RFID Privacy Study

The story seems simple enough. An outside privacy and security advisory committee to the Department of Homeland Security penned a tough report concluding the government should not use chips that can be read remotely in identification documents. But the report remains stuck in draft mode, even as new identification cards with the chips are being announced.

Jim Harper, a Cato Institute fellow who serves on the committee and who recently published a book on identification called Identity Crisis, thinks he knows why the Department of Homeland Security Data Privacy and Integrity Advisory Committee report on the use of Radio Frequency Identification devices for human identification never made it out of the draft stage.

"The powers that be took a good run at deep-sixing this report," Harper said. "There's such a strongly held consensus among industry and DHS that RFID is the way to go that getting people off of that and getting them to examine the technology is very hard to do."

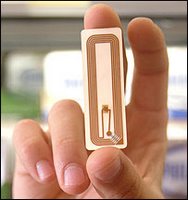

RFID chips, which either have a battery or use the radio waves from a reader to send information, are widely used in tracking inventory or for highway toll payment systems.

But critics argue that hackers can skim information off the chips and that the chips can be used to track individuals. Hackers have also been able to clone some chips, such as those used for payment cards and building security, as well as passports.

The draft report concludes that "RFID appears to offer little benefit when compared to the consequences it brings for privacy and data integrity" -- a finding that was widely criticized by RFID industry officials when the committee met in June.

Meanwhile, the RFIDs just keeping coming. Last week, the State Department announced that it would soon be issuing new cards for visitors to Mexico, Canada and the Bermudas containing a chip that could be read from 20 feet away.

Changes in federal law will require Americans to have either a passport or the new "PASS card" to re-enter the country by air in 2007. Currently a driver's license will suffice to get an American back inside the country from these neighboring spots, but starting in 2008 that won't suffice even for quick, cross-border jaunts by car.

RFID chips are being used in the nation's passports, cards used to identify transportation workers and cards for federal employees, and may be features of the Registered Traveler program, the soon-to-be-released standards for all states' driver's licenses under the REAL-ID act, as well as proposed medical cards.

In early October, the Center for Democracy and Technology, a civil liberties group known for partnering with industry groups, submitted comments criticizing the draft report, calling for a deeper factual inquiry and analysis, and a broader focus on identification technologies generally.

Jim Dempsey, the policy director for the CDT, says his group doesn't want the report killed -- he just thinks the privacy committee is ignoring the reality that RFID-enabled identification is already here. The report should focus on how secure the cards are, how far they can be read from and the whole backend of how data is stored and shared.

"Basically we were raising a flag on the one hand saying that RFID is already being deployed and we can no longer take the finger-in-the-dike approach," Dempsey said. "And we were saying that RFID is only one facet and not necessarily the most troubling aspect of this broader evolution of the creation and management of identification. The implications are huge, and to focus on RFID is, in that sense, off-target."

For instance, when customs agents begin reading the new PASS cards at the border, the travel data will be stored for up to 50 years, will be shared within Homeland Security and will be made available to law enforcement groups, both domestically and internationally, according to DHS' own privacy assessment.

It's unclear whether the new cards will have encryption or other measures to prevent skimming or forgery. That decision was left to the State Department, which will produce the card and has thus far remained mum on the privacy issues.

Harper hopes the committee will vote to finalize the report and that it will have an effect on the design of the PASS card, which currently proposes to let a Customs officer read them from 20 feet away.

"If we don't have a report out before the (PASS card) comment period ends, then we are irrelevant," Harper said.

Labels: Political Statements, Tech News

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home